Extra! Extra! There is a single (unified) framework for exclusionary abuses under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”) consisting of a single standard of proof and a single legal test: the enforcer/claimant needs to establish that the plausible objective rationale (considering all the relevant circumstances) behind a dominant company’s conduct [standard of proof] is for the dominant company to derive an advantage (i) through means that equally efficient competitors cannot replicate to derive a comparable advantage, including means that are specifically designed to foreclose equally efficient competitors [“competition on the merits”/artificiality limb of the test]; and (ii) that equally efficient competitors cannot offset by other means, so they would be potentially foreclosed as a result [potential foreclosure effects/“capability to foreclose” limb of the test]; unless the dominant company proves that the advantage is either replicable or offsetable (as a matter of procedure or substance depending on the interpretation of C-413/14 P Intel), or provides an alternative explanation or an objective justification. This is the subject of my paper Quantum Antitrust – A Unified Exclusionary Abuse Theory that has just been published in open-access form in the IIC – International Review of Intellectual Property and Competition Law.

Owing to the Darwinian nature of competition law, which only applies where market failures (i.e., “artificialities” making the interplay of supply and demand lead to an inefficient market outcome) materialise, relative efficiency is the common quantum of any competitive assessment. In other words, since there is no market failure/artificiality in the departure of less efficient companies (actually there would be a market failure if less efficient companies were to thrive), there is identity between the relative efficiency criterion and the very concept of market failure, which means for companies to obtain a competitive edge from a source other than their own efficiency (superior price, quality, innovation or choice) and thus artificial (either by reducing competitive uncertainty through collusion, or leveraging market power). Hence, to achieve their goal of avoiding market failure, competition rules must apply the same competition-on-the-merits/efficiency standard to both (i) the dominant company for its conduct to be legitimate and (ii) its competitors to be worthy of protection. This is the real level playing field that competition rules need to secure to limit themselves to preventing market failure rather than predetermining a market outcome (such as the efficiency-agnostic prophylactic objectives of fairness and contestability to be achieved by means of regulation – i.e., the Digital Markets Act), that is, to ensure the equality of opportunities, rather than results, underlying market economy.

Therefore, every competition law assessment in the field of exclusionary abuse boils down to ascertaining whether the raison d’être (in the sense of objective nature or economy rather than mere subjective intent, which is of course not decisive in abuse of dominance – e.g., C‑549/10 P Tomra) of the dominant company’s conduct can plausibly be to derive an advantage that competitors cannot replicate (thus not based on their merits) or offset by other means (thus potentially resulting in foreclosure). Such an epistemological or cognitive state in the dominant company’s mind is objectivised by holistically judging the dominant company’s conduct against the backdrop of the relative efficiency of its competitors: failing only one of the two elements of the test (if either the conduct does not afford the dominant company an irreplicable advantage or, even if it does, competitors can defeat it by other means to stay in the market) the conduct is not illegal. This analysis is made in light of the objective features of the conduct and “all the relevant circumstances” surrounding it (C-413/14 P Intel, para. 142), including the presence of less efficient competitors increasing the overall competitive pressure (this is what the Court meant in C-23/14 Post Danmark II, para. 60, rather that the wrong reading in the Opinion in C-48/22 P Google Shopping, para. 195).

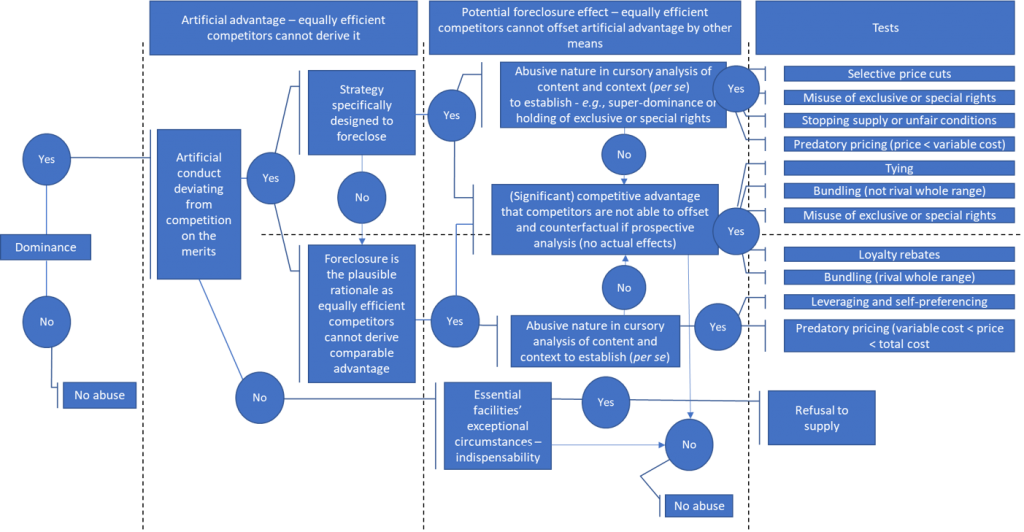

As a result, both limbs of the unified exclusionary abuse test (competition not based on the merits/artificiality/advantage that equally efficient competitors cannot replicate, on the one hand, and potential foreclosure effect/advantage that equally efficient competitors cannot replicate or offset by other means, on the other) are one and the same. By the same token, the seemingly different abuse tests defined in case law (tying, bundling, predatory pricing, loyalty-enhancing rebates, margin squeeze, refusal to supply, etc.) are just case-specific manifestations of the single test concretising the factual points to be proven in each scenario to establish that its both limbs are fulfilled (like points in a continuum), as shown in the following table from the paper:

Depending on the extent to which each of these two limbs can be presumed based on economic judgment or a rule of experience or is not self-evident so it needs to be proven, all those seemingly different classic abuse tests can be classified in a continuum (as the test is in reality just one), from the legitimate decision not to deal subject to the essential facilities doctrine to per se abuses. This allows to reconcile both the “more economic” approach with the necessary per se rules and the assessment under Article 101 TFEU and under Article 102 TFEU (as doctrine is finally vindicating – P. Ibáñez Colomo, 2024a). In the following table from the paper, all classic abuse tests are classified in four quadrants depending on whether both the exclusionary object and the foreclosure effect are clear, the exclusionary object is clear but the foreclosure effect is not, there is no obvious exclusionary object but the foreclosure effect is clear, or there is no obvious exclusionary object or foreclosure effect:

The single exclusionary abuse framework based on relative efficiency is so obvious (at least from margin squeeze cases and, in particular, C-280/08 P Deutsche Telekom) as it is baffling that until C-377/20 SEN and C-680/20 Unilever (and even right afterwards) the mainstream doctrinal stance was that any unifying endeavours were futile. Actually, the Court of Justice has already asserted that there is only one standard (Balance of probabilities) and test (significant impediment to effective competition) in merger control – what varies from case to case is just the quality of the evidence that is required to meet that single standard and test depending on how direct or indirect the chain of cause and effect behind the theory of harm is (C-376/20 P CK Telekoms).

We have witnessed the same resistance in doctrine, which, however, has evolved in the right direction. For example, P. Ibáñez Colomo, 2021, pp. 2-3, reads “there is no such thing as an all-encompassing approach or test to identify abuses”, while P. Ibáñez Colomo, 2023a, pp. 20-21, already acknowledges that [the “as-efficient competitor principle” gives] “an operational meaning to the notion of competition on the merits” that allows us to establish the abuse in all cases, or, at least, those not having a clear anticompetitive object (P. Ibáñez Colomo, 2023b). Then, some months later, the author eventually recognised (and I could not agree more) that such relative efficiency benchmark is equally applicable to these “by object” or per se abuses – where it is precisely the applicability of that benchmark that entails that the exclusionary effects of a strategy specifically designed by the dominant company to foreclose any (and thus including equally efficient) competitors will necessarily be causally linked to this practice without need to disprove that the cause of foreclosure was the lower efficiency of competitors (P. Ibáñez Colomo, 2024b). No to be blamed considering that certain members of the Court have not realised this yet (see my comment on the Opinion in C‑48/22 P Google Shopping). Other authors are progressively starting to give the relative efficiency criterion the credit that it deserves at the centre of a unified exclusionary abuse standard and test (see, e.g., G. Gaudin and D. Mantzari, 2022, proposing a non-price version of the “as-efficient competitor test” to operationalise both the artificiality and the potential exclusionary effect of the conduct, or Pınar Akman, 2024, referring to some “as-efficient competitor standard” to reconcile the “more economic” approach with per se abuses.

Although those are really useful steps, they are still partial, and, to my knowledge, surprising as it may sound, nobody has gone as far as to asserting that relative efficiency (I do not like the expression “as-efficient competitor principle” which is associated with the abovementioned fragmentary approach) is the key to a unified exclusionary standard and test that features the following advantages, as I claim in my paper: (i) it makes sense of previous case-law; (ii) it gives the notion of abuse the objective nature required to fit with the legal content of Art. 102 TFEU (i.e., the special responsibility); (iii) it solves the causality problem by allowing the causal link to be between dominance and conduct, instead of between dominance and effects, (iv) it makes deviations from competition on the merits objective, thereby reducing competition authorities’ arbitrariness in this regard and enabling judicial review, (v) it bridges the gap between the assessment of abuses and agreements, as well as between the more economic approach and per se rules (to be applied in the form of a cursory analysis inspired by the analysis of the degree of harm necessary to establish restrictions by object under Art. 101 TFEU), and facilitates recourse to the single and continuous infringement device; and (vi) it helps strike a balance between, on the one hand, the general interest in competition and, on the other, the dominant company’s rights to property, freedom to conduct a business and economic incentives to innovate and invest, which are ensured by the essential facilities doctrine. For more details, you would need to read the article!